YOUR BUSINESS AUTHORITY

Springfield, MO

YOUR BUSINESS AUTHORITY

Springfield, MO

Now, it’s the law: Employers must make reasonable accommodations for employees with conditions related to pregnancy and childbirth.

The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, signed into law by President Joe Biden on Dec. 29, came into effect June 27. Under its provisions, both public- and private-sector employers with 15 or more workers must provide accommodations to pregnant workers unless the accommodations would cause the employer undue hardship.

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which is tasked with enforcing the new law, already enforces laws making it illegal to fire or discriminate against workers on the basis of pregnancy or childbirth. Companies with 15 or more employees are covered under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, and the new law extends its protections to pregnant workers.

The law applies to childbirth pre- and post-partum conditions related to pregnancy, including infertility treatment, abortion care, morning sickness, caesarean section care and post-partum depression.

Sara Choate, managing director of Human Capital Solutions at KPM CPAs & Advisors, offered a few examples of reasonable accommodations, or changes to the work environment or processes, that the law might permit:

The law spells out that employees do not have to accept a suggested accommodation without first discussing it with the employer. Employees cannot be required to take leave if a reasonable accommodation can be provided that would let them keep working, and employees cannot be denied a job or opportunity based solely on the need for an accommodation, Choate explained.

“I think it’s going to be a pretty big game-changer for employees and employers, but it’s a little bit under the radar at the moment,” Choate said.

She said some conditions experienced during pregnancy can very obviously fall under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Gestational diabetes and preeclampsia, or pregnancy-related high blood pressure, are two examples.

But before the PWFA was passed, other conditions were hazier.

Choate gave the example of morning sickness – not an obvious disability, yet it can be debilitating.

“What this does is kind of help close that gap a little bit and provide protection for people who are experiencing it,” she said.

She clarified that the law covers conditions related to pregnancy and childbirth.

“Being pregnant is not what it covers,” she said. “The condition of being pregnant is not considered a disability.”

Prior to passage of the PWFA, Choate said an employer might choose to treat a pregnant person the same as any other employee, including in those cases where an accommodation might be reasonable. She gave the example of a pregnant employee having to walk a long distance from a parking area.

“Now, it opens the door for some of those things to be considered,” she said.

She noted that if doing so is not unreasonable for the position, additional paid bathroom or water breaks must be provided if requested.

Additionally, if a job requires a pregnant employee to stand for eight hours a day and the worker requests a stool, the employer must consider providing one if that is a reasonable accommodation.

You’ve come a long way

Before the United States achieved independence, the colonies operated under English law that did not allow women to keep money they earned from working – or even to own property. After statehood, women could not advocate for their own self-interest in the voting booth, as they did not earn the right to vote until the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified in 1920.

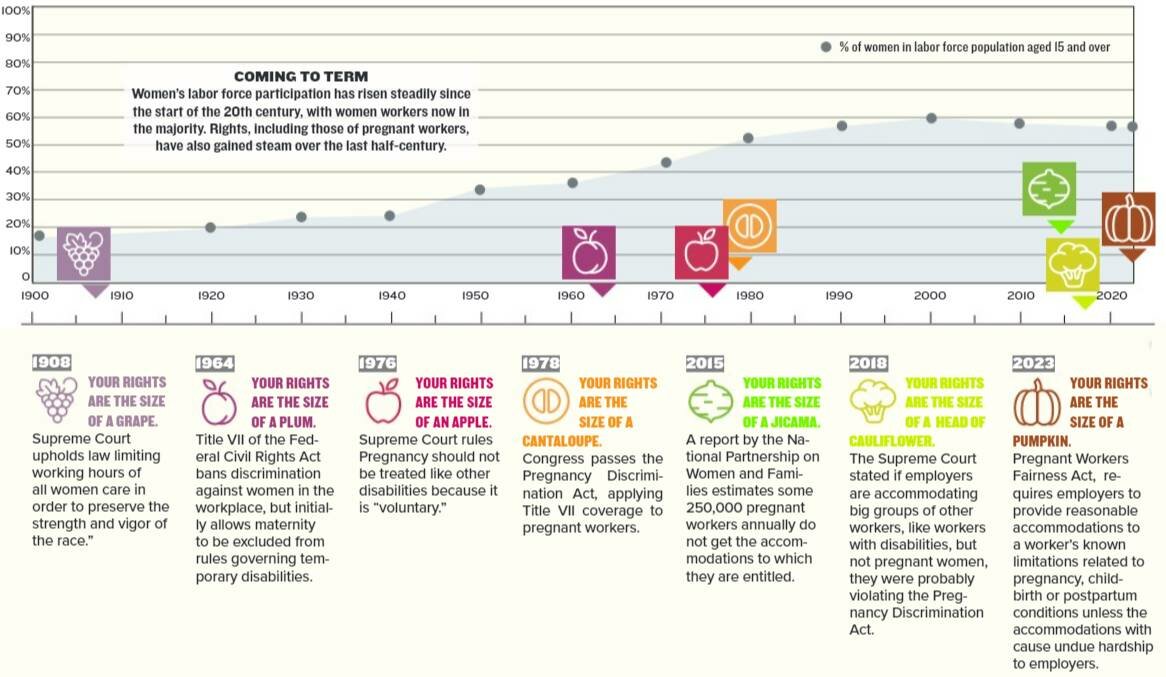

In 1908, women’s working hours were limited by the U.S. Supreme Court, which found that women’s physical well-being was “an object of public interest” since their health was “essential to vigorous offspring.”

It was not until 1964 that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act codified equal rights for women in the workplace.

Women gained more rights as the 20th century progressed, with the Pregnancy Discrimination Act’s passage in 1978. That law applied Title VII to pregnant workers, and employers were required to treat them the same as nonpregnant workers who were similar in abilities.

Before passage of the PWFA, the Supreme Court determined in its 2015 decision, Young vs. UPS, that pregnant workers were entitled to accommodations if they could prove another worker had been given accommodations for similar physical limitations.

The PWFA could benefit up to 2.8 million workers annually, according to the National Partnership for Women and Families, an advocacy organization.

In a statement following House passage of the act in 2021, President Biden said, “Across our country, too many pregnant workers are forced to choose between their health and a paycheck.”

The act was supported by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which noted employers had faced uncertainty about whether and how to accommodate pregnant workers prior to passage of the law.

ADA mindset

Lynne Haggerman, owner of human resources and business consulting firm Lynne Haggerman & Associates LLC, called the PWFA “a good thing.”

Haggerman said she has been an HR consultant for a quarter of a century and has seen a great deal of positive change, and the new law is a prime example.

Still, Haggerman said the law will likely pose some challenges for small businesses.

“I don’t think I can name one law that’s not difficult for a small business, but it’s like baseball – you learn the rules and play the game,” she said.

Haggerman offered a basic rule of thumb to help small businesses adapt to the new law, and that is to think of the ADA.

“They’re used to accommodating for the Americans with Disabilities Act – they’re very familiar with that, and this is similar in many ways,” she said.

In a small business, accommodating one worker could mean that others have to pick up the slack, she said.

“In this community – in southwest Missouri – the vast majority of business owners are super caring. They’re truly trying to do the right thing and trying to help people,” she said. “I’ve seen companies go way above and beyond the call.”

She said things get tricky when a worker can’t perform essential functions. If a job that is typically done standing, such as on a factory line, can be performed instead from a tall chair, that is a reasonable accommodation.

Alternately, a restaurant server cannot perform the functions of the task while seated.

“If they’re required to stay off their feet, there’s nothing in the world you can do with that particular job,” she said. “You can’t allow a waitress to sit and still call that person a waitress.”

Other reasonable accommodations might be possible, however, she noted; for instance, work hours could be reduced, schedules could be changed, and the worker could be put into a different position, such as hosting, temporarily.

And that word, “temporarily,” is an important distinction to pregnancy-related disability.

“If a doctor says a waitress has to go on bedrest, normally, company policies would kick in about sick days, vacation days and disability to help the person get past this to where they’re back at work,” she said.

The EEOC will provide examples of accommodations and interpretations of the law through the end of the year, according to the legislation.

The commission is accepting complaints now, and workers may submit a complaint through its website. In general, complaints must be filed within 180 days.

Haggerman said prior to passage of the PWFA, Missouri offered some protections for pregnant workers and applicants through the Missouri Human Rights Act. That state anti-discrimination law was first adopted in 1957 and updated in 2017.

Haggerman said she recommends companies apply their existing ADA policies and practices to pregnant workers.

“There are some nuances,” she said, “but the big benefit of this is although it’s not part of the ADA, it borrows so much terminology and practices from the ADA that it clarifies things for people. That’s going to help employees who are pregnant.”

A franchise store of a Branson West-based quilting business made its Queen City debut; Grateful Vase launched in Lebanon; and Branson entertainment venue The Social Birdy had its grand opening.

$2M in tax credits awarded to SWMO nonprofits

Baldwin, Lathan to chair United Way campaign

Produce recall impacts food sold at Walmart, Aldi and Kroger

Mixed-used development proposed in KC area

Tax deduction program for farmers set to launch

Report: Panera explores sale of Caribou Coffee, Einstein Bros Bagels