YOUR BUSINESS AUTHORITY

Springfield, MO

YOUR BUSINESS AUTHORITY

Springfield, MO

Owner: Terry Chase

Founded: 1973

Address: 205 Wolf Creek Road, Cedarcreek

Phone: 417-794-3303

Web: ChaseStudio.com

Email: info@chasestudio.com

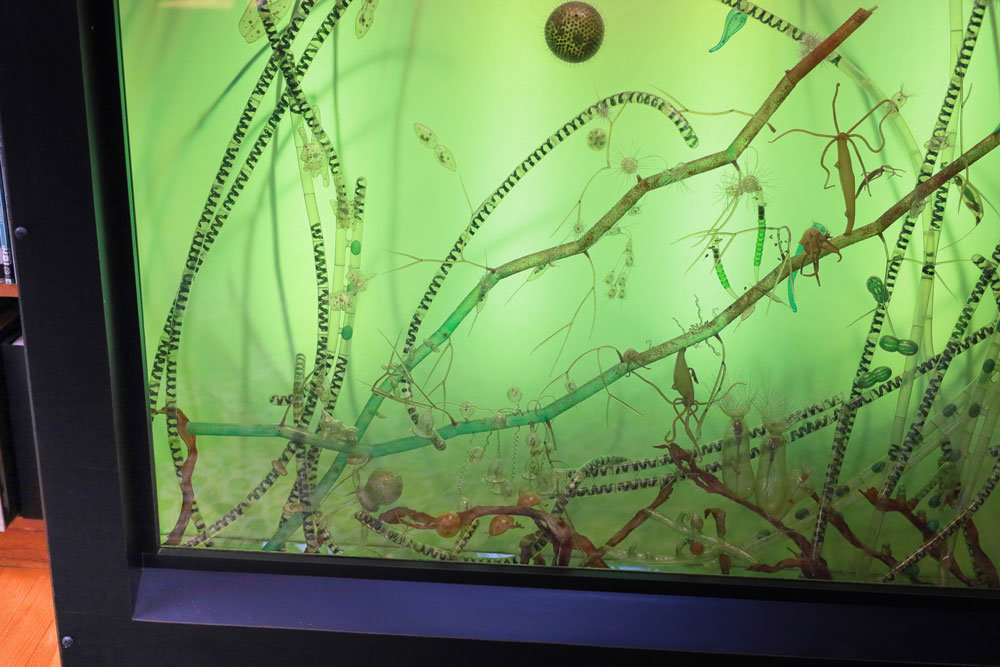

Services/Products: Natural history exhibition design and construction

Employees: 20

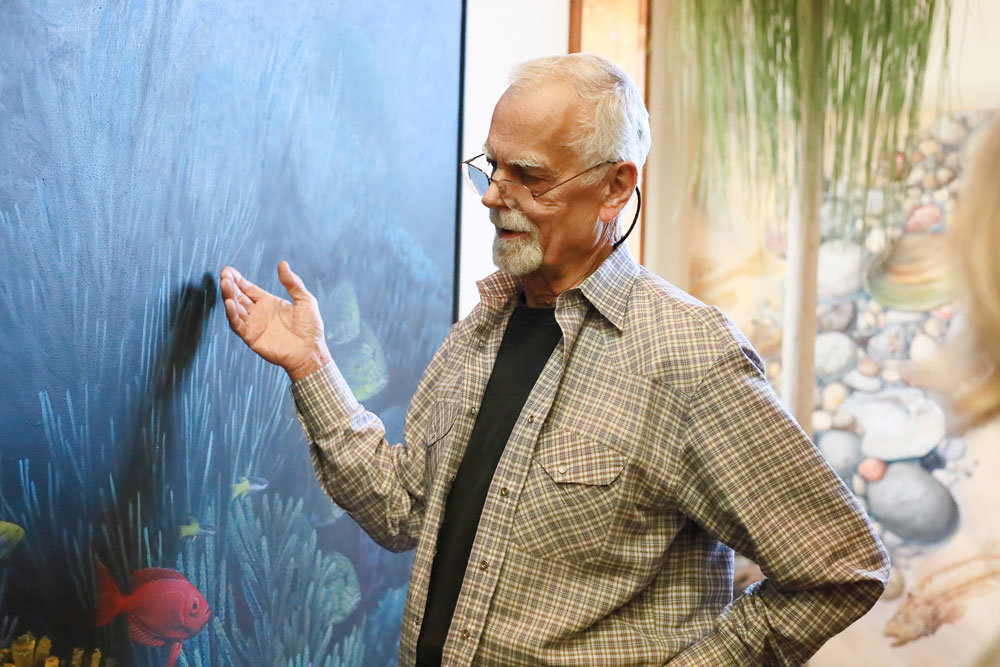

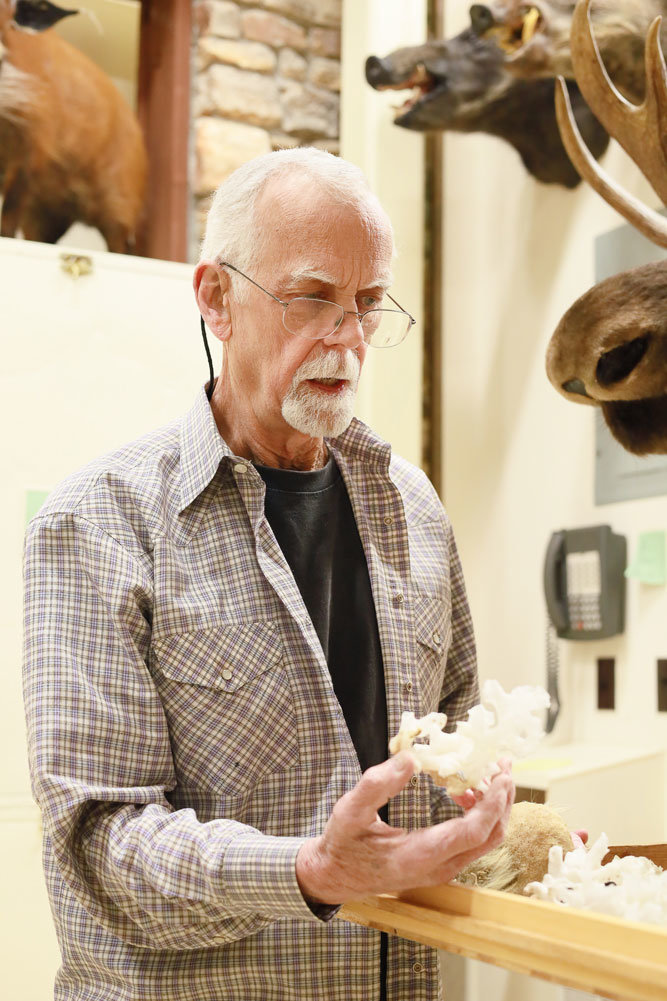

Hidden away on 1,500 acres in southern Missouri sits Chase Studio, a sprawling workshop of scientist and artist Terry Chase. His name may not be immediately recognizable, but the same can’t be said of his work.

“Millions of people every week see our exhibits,” Chase says. “It’s amazing that we’re tucked down here in the middle of nowhere and nobody knows about it, nobody knows about me.”

Chase’s work spans 50 years and hundreds of museums and exhibit centers worldwide that specialize in natural history, including The Smithsonian Institution and Chicago’s Field Museum, and locally, a number of the state park visitor centers in Missouri and Arkansas.

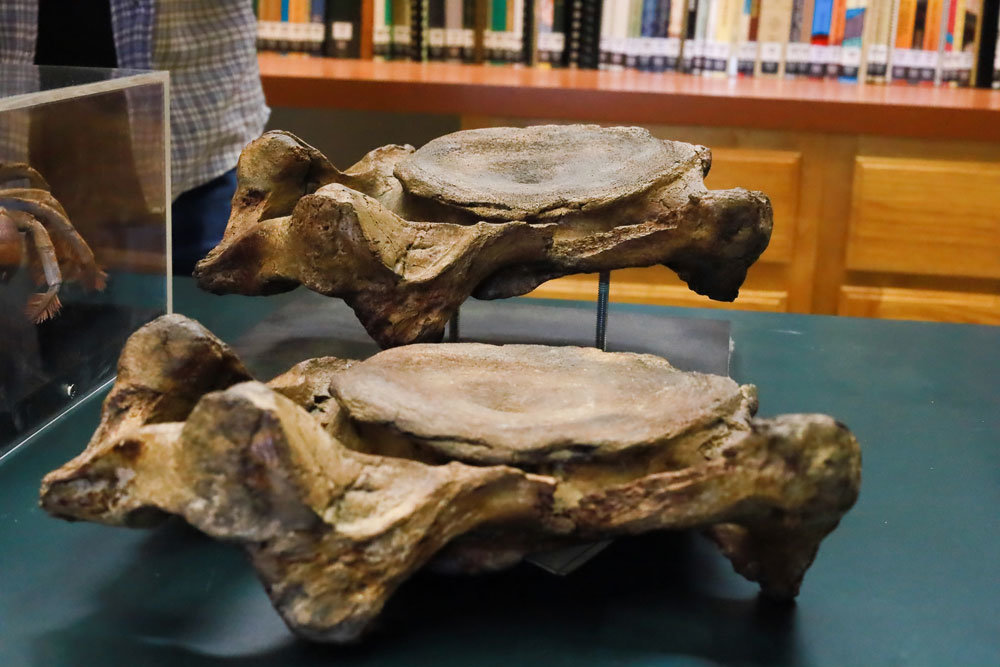

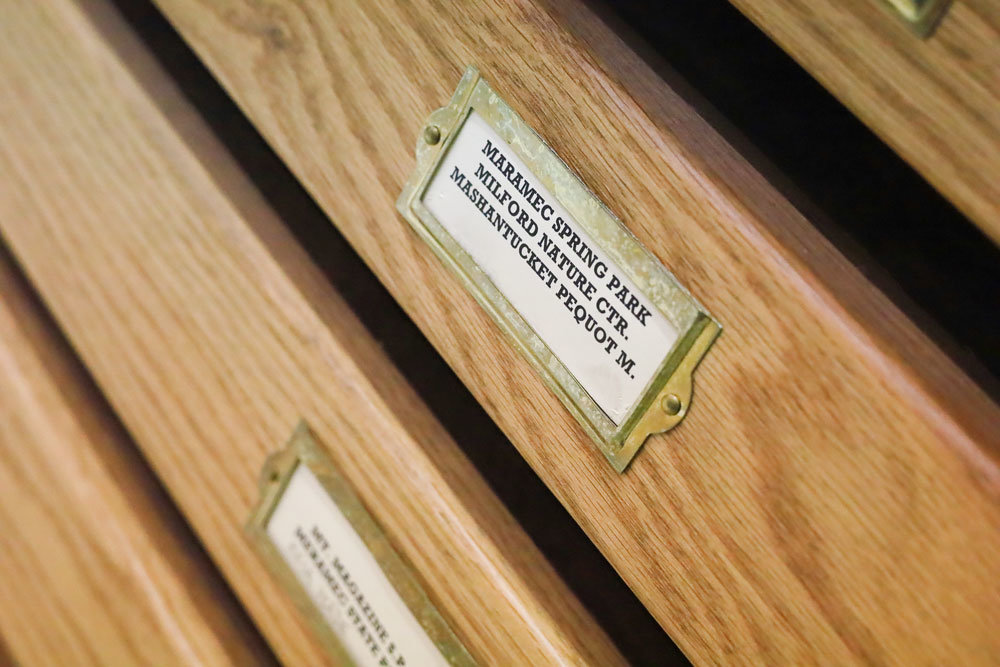

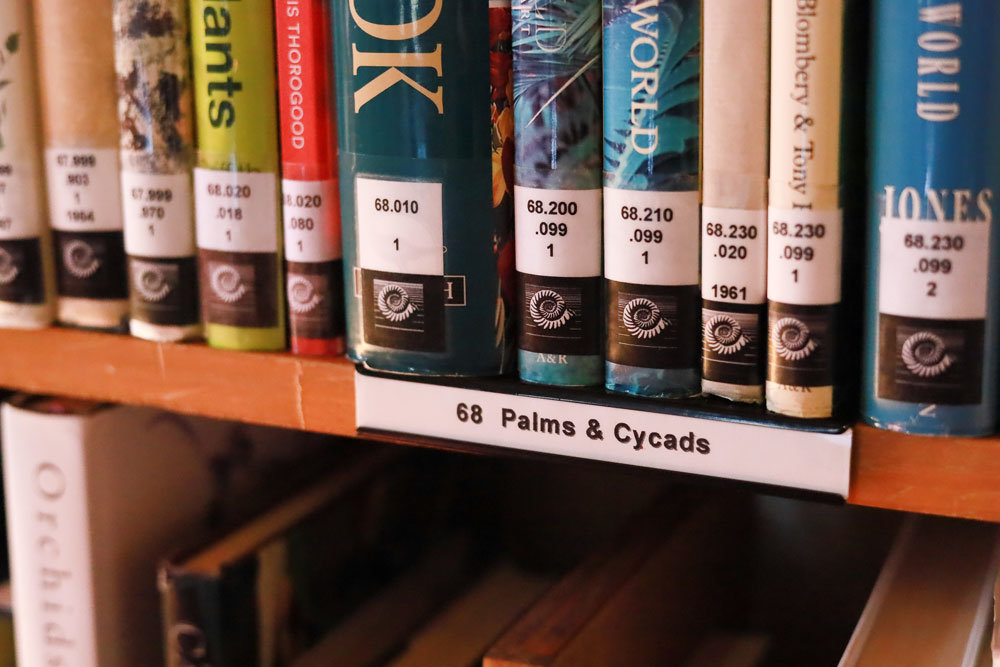

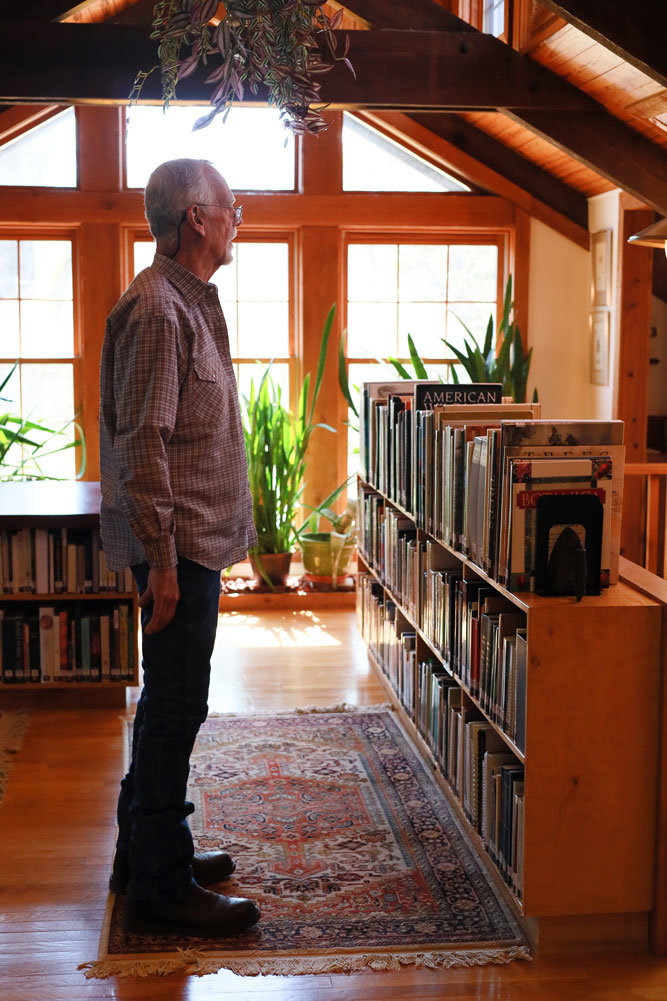

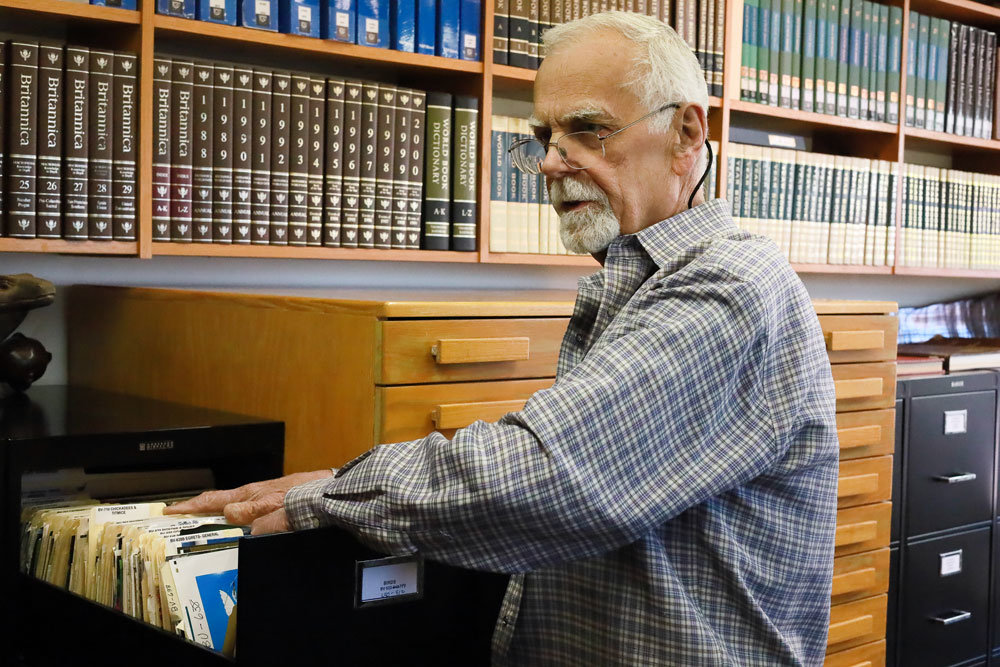

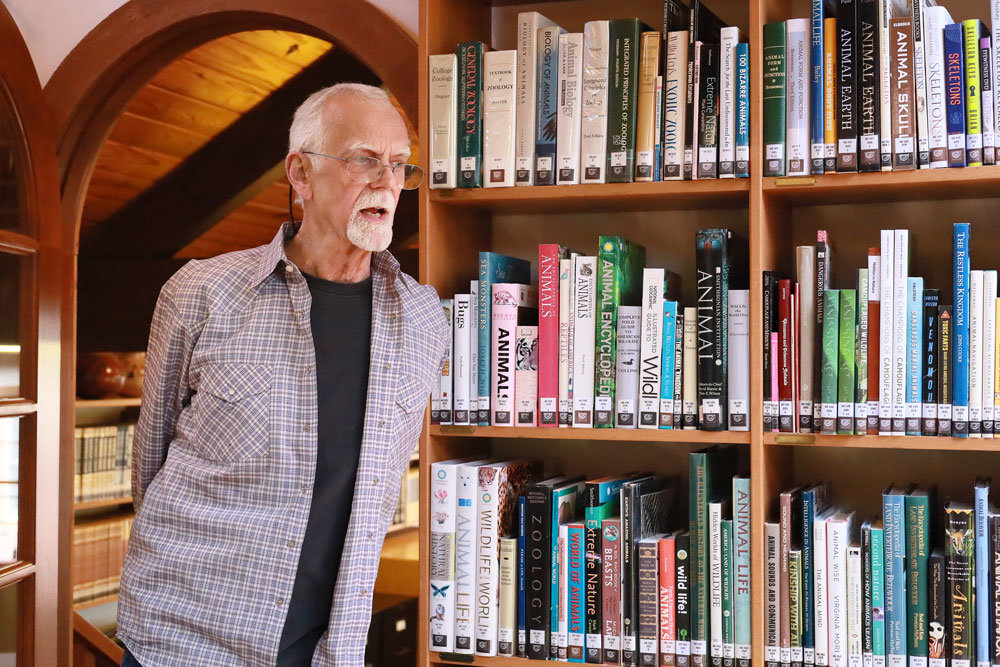

Chase, who holds a master’s degree in paleontology from the University of Michigan, has a passion for art and science and has combined the two areas to create a distinguishable career in creating museum exhibitions. He has employed up to 90 people at his studio, including artists, sculptors, scientists, cabinet makers, welders and even an on-site librarian, to manage the collection of over 20,000 books on natural history.

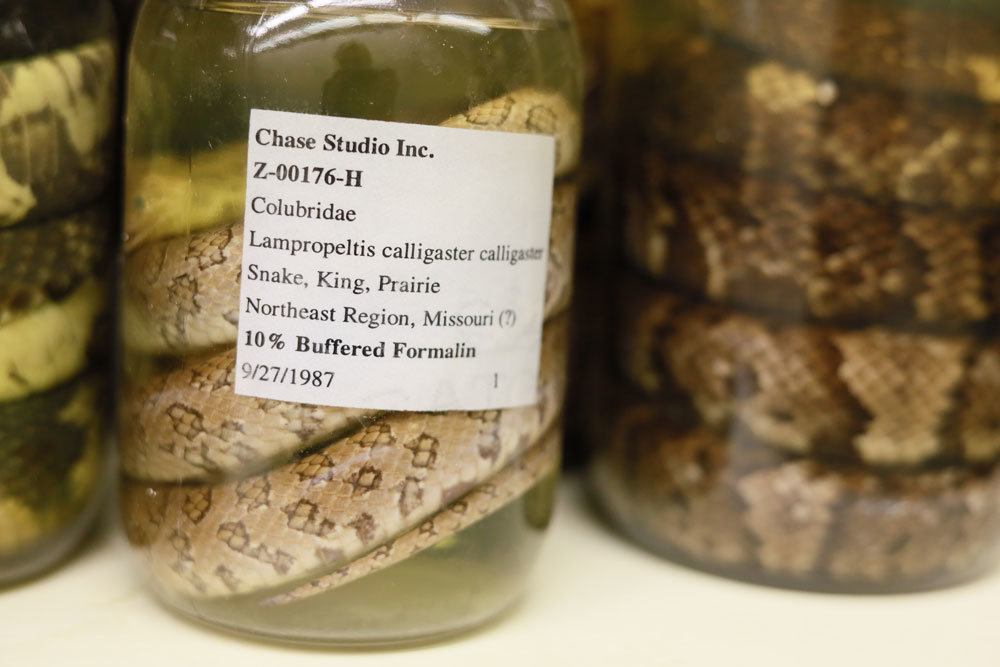

“We have the reputation that we do because of our scientific background,” Chase says.

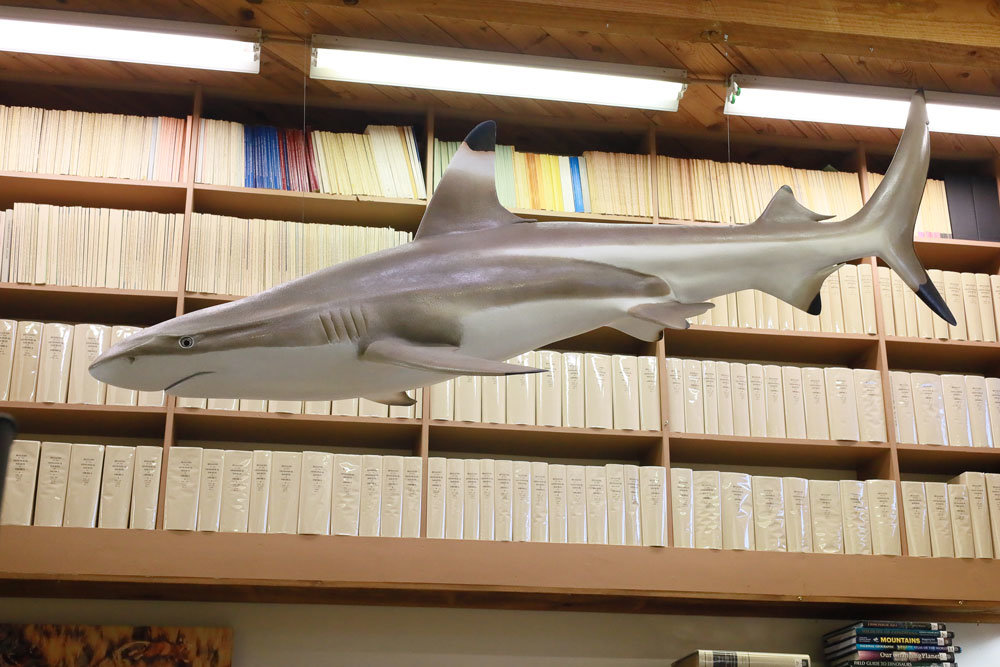

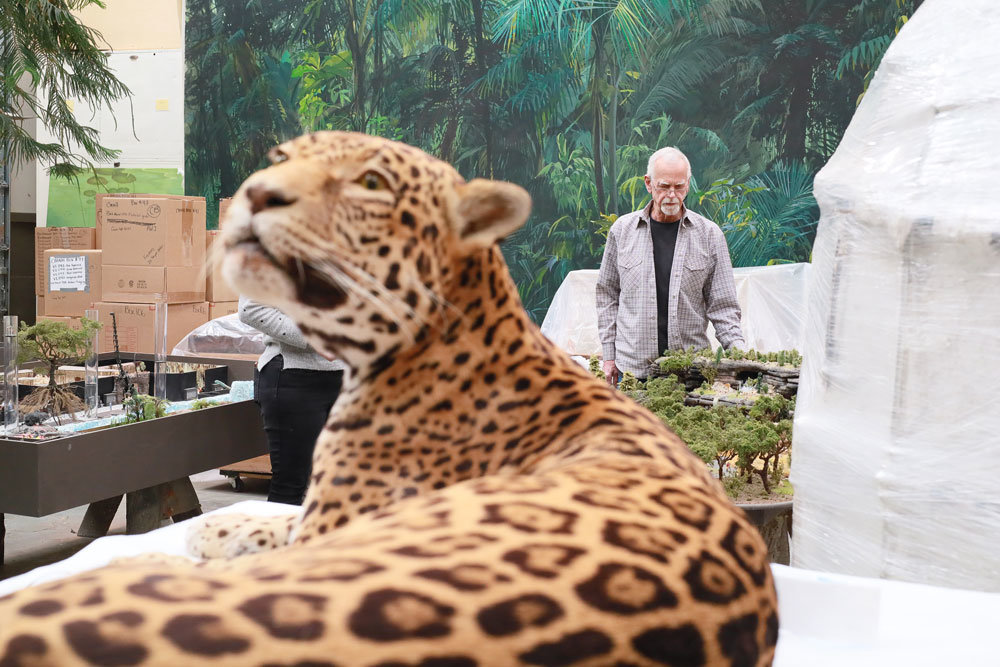

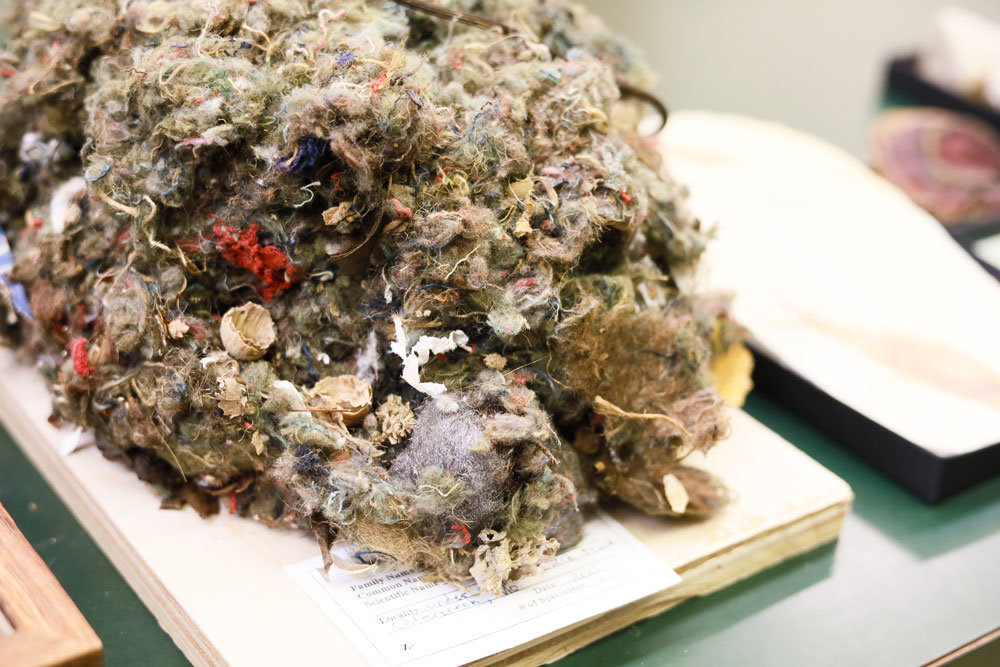

The studio and workshop, a complex of 11 buildings and 50,000 square feet of workspace, also contains a private collection of over 1 million natural history specimens, including rooms painstakingly archived with a variety of fossils, rocks and minerals, corral specimens, taxidermy animals and folk art from across the globe.

One of his most recent projects, completed in January, was the restoration of a papier-mache life-size model of a 14-foot giant Pacific octopus for Harvard University. The octopus originally arrived on its campus in 1883, and after years of existing in less-than-ideal conditions in a classroom at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, Chase was hired to help move and restore the specimen.

Financed by the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Chase worked closely with Sylvie Laborde, acting director of exhibitions for the Harvard Museums of Science and Culture. Laborde says that Chase’s restoration process, which cost roughly $15,000, required maintaining the papier-mache technique, which isn’t commonly used in modern model-making.

“Terry had to adapt, and he did an amazing job,” says Laborde, down to matching the original painting techniques. “Terry was trying to match as close as possible this effect, but he didn’t have the history of how it was created. He adapted his own paintbrushes to create the same spotty texture.”

Working on an animal spanning 14 feet is the tip of the iceberg for Chase.

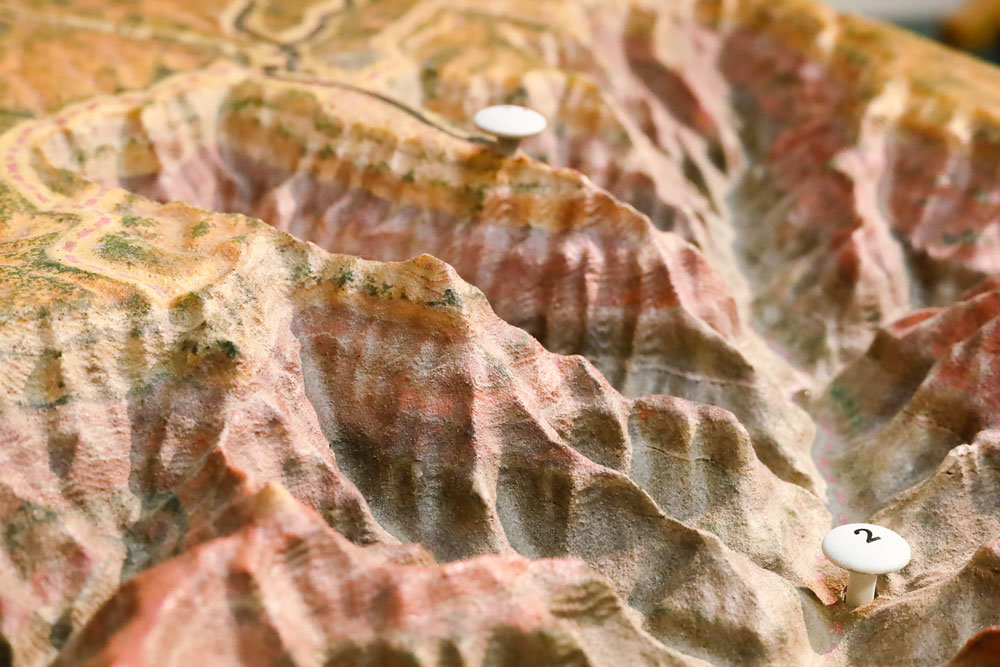

“We’re getting ready to start on an 85-foot cottonwood tree for the Denver airport,” he says. Building a tree to that scale requires multiple steps, many of which Chase and his team have developed over the years, including welding the trunk and branches from steel before layering with naturalized textures to create a realistic effect.

“Our botanical models are so realistic, it’s hard to tell them from the real thing,” Chase says. Using a homemade machine that he says performs better than commercial options, Chase makes molds directly from the plant parts and vacuum-forms foliage in plastic to create perfect replicas. Chase says he is a perfectionist, like many on his team.

“I’m more interested in perfection than money,” he says, declining to disclose annual revenues. “People ask me ‘how much do you charge?’ I have no idea.

“I have to have people that watch over me because I tend to give stuff away for free.”

Chase says he and the studio staff of 20 – including Business Manager Linda Clark – typically work on a dozen projects at a time, some of which take years of planning and execution.

This summer, he’ll accept and employ up to eight college students in an immersive internship experience where they’ll learn natural history model building.

The program is a partnership with Missouri State University, where Chase has donated 1,200 acres of his property for the university’s biological field station. It now houses an Environmental Education Center that includes classrooms, a commercial kitchen and dorms for up to 25 students.

Laborde hopes the internship program is a way for future artists and scientists to learn not just about model-making but also absorb Chase’s passion that goes into this specific style of work. “Terry understands space very well, and designing an exhibit with him is not just about model-making; he understands the science and biology,” she says.

Chase has enough projects to fill his 15-hour workdays, including a recent commission by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where he is restoring over 300 taxidermy animals. One project that he is particularly excited about, however, is a traveling exhibit called “The Art of Chase Studio,” where his team of artists will display individual pieces. Chase says the Draper Natural History Museum in Wyoming has committed to the first exhibition, and he’s hoping to display regionally at the Springfield Art Museum as well.

“My wish list is a mile long,” Chase says, noting it includes plans for constructing a natural history museum in the Ozarks with potentially 350,000 square feet of interactive exhibit space, an outdoor arboretum and a scientific collection repository. “I’ve been doing this for 50 years, and it’s almost an obsession. I love what I do. That’s what keeps me going.”

Other stories that may interest you

Moseley’s Discount Office Products was purchased; Side Chick opened in Branson; and the Springfield franchise store of NoBaked Cookie Dough changed ownership.