YOUR BUSINESS AUTHORITY

Springfield, MO

YOUR BUSINESS AUTHORITY

Springfield, MO

Last edited 8:21 a.m., Oct. 3, 2023 [Editor's note: Nancy Allen is not the author of the children’s book “Everyone Eats.” She was misidentified in a database by developer Vercel of works used to train artificial intelligence platforms.]

In New York, the heart of the nation’s publishing, a group of some of the world’s prominent authors filed a lawsuit Sept. 19.

The case filed in the United States District Court-Southern District of New York pits the 9,000-member Authors Guild, the nation’s oldest professional organization for writers, against OpenAI Inc. and its for-profit subsidiary OpenAI LP, owner of ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence chatbot.

At issue: Works by many of the members of the Authors Guild are being used without permission to train algorithms at work in OpenAI chatbots to produce writing on demand – meaning that the product coming out of ChatGPT and similar programs is modeled after the singular human imaginations of Authors Guild plaintiffs like John Grisham, Jonathan Franzel, Jodi Picoult, George Saunders and Scott Turow.

In the Ozarks, New York Times bestselling author Nancy Allen was going about her business – primarily writing and thinking about writing – when Springfield Business Journal contacted her with the news that her own literary work was used to train AI chatbots.

Allen’s first response to a social media message was a shocked and not-appropriate-for-publication internet slang acronym.

“I didn’t know,” she added. “I thought it was just Grisham, [Michael] Connelly, Jodi Picoult, etc.”

Allen’s name showed up in a database by Vercel, a platform for front-end developers, that lists work used to train Vercel’s AI platforms. When users put in a request for marketing text, a white paper, an English class essay or even a novel, they can thank Allen and other writers for what comes out. Her novel, “A Wolf in the Woods: An Ozarks Mystery,” is part of the AI mix.

Changing landscape

Corey Kilburn, an intellectual property attorney and founder of the Springfield law firm RoundTable Legal LLC, said copyright – the crux of the Authors Guild lawsuit – is complicated, and when it comes to AI, everything is in flux.

He said copyright law traditionally protects original works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible expression or medium. It’s designed to incentivize creativity by granting exclusive rights over a period of time – typically, the life of the author plus 70 years. The copyright realm applies to literary works, music, visual art and even source code created by programmers. As currently interpreted, copyright does not apply to AI output.

“It includes only human authorship,” he said. “The question in current case law is if that’s going to be the rule of thumb moving forward.”

Kilburn said rights associated with copyright include protection of works from being copied, but also include a bundle of other rights, such as the right to prevent others from publicly performing or displaying an author’s work.

Those rights also exclude others from making derivatives of a creator’s work, and that issue is directly applicable to generative AI.

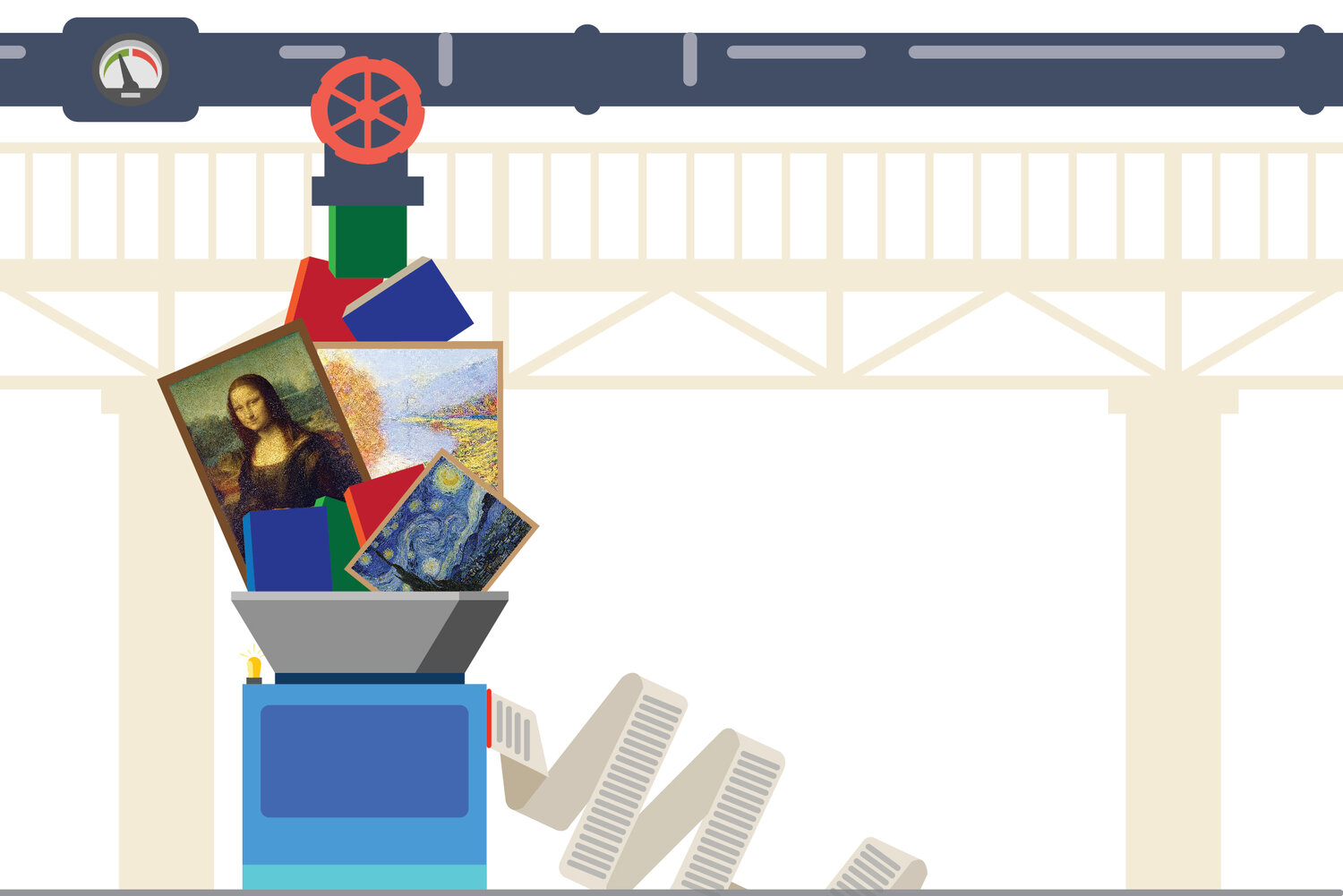

Kilburn said AI systems process data that’s been fed into a program to create what is essentially a new piece of visual art, music or literature.

“All of these things can happen based on the guidance and directive put in there by the operator,” Kilburn said. “Is the derivative work substantially similar to these other works that they’re trying to use as sources? That’s the big question right now.”

Kilburn gave the example of an AI-generated work of visual art.

“If you put in all the works of the great masters, like [Vincent] van Gogh and [Claude] Monet, and some current artists, and AI then generates new work based upon that, is the new work entirely a creation of AI? Is it a creation of the parameters set by the user, or is it derivative work?” he said.

The challenge, he said, is distinguishing between derivative work and work that is created in the style of another artist – something that copyright law allows.

Artists have a long tradition of working in the style of another creator, often as a learning activity or a way of honoring an influence, he noted.

“The distinction is this AI generative product can really mimic it,” he said. “It almost seems exactly like the author is putting out this new work with no distinction.”

As technology advances, the law can be caught flat-footed, according to Kilburn.

“Do we look at this in the same lens of traditional copyright, or do we need to create a new form of copyright protection for AI?” he said.

The European Union is currently creating new regulations concerning AI, he said, and the U.S. Copyright Office – part of the Library of Congress – is also taking up the issue by seeking input from creators.

Courts to decide

Allen, who is also a lawyer and the former assistant Missouri attorney general, said she supports the Authors Guild and its fellow plaintiffs in what has become a class-action lawsuit.

“It sounds like a flagrant violation of the Copyright Act and is not a fair use of the author’s creative work,” she said.

To some, AI is progress and inevitable, she added.

“In my opinion, if they can’t make AI books without stealing the creative work from a writer, the courts need to step in,” she said.

Aliki Barnstone is a professor of creative writing at the University of Missouri. She is also a poet, translator, memoirist and visual artist.

Barnstone said it’s not just best-selling work being used by AI; reporting in The Atlantic noted 183,000 books have been put to this use.

“We writers want to be quoted and cited. It’s not just because we want the money – and commonly when we’re quoted there’s a fee, even for a few lines of poetry,” she said via email. “There are rules about fair use.”

As a professor, she is not permitted to copy books and put them up on teaching platforms, she said – there are limits to materials she can use to train her students.

“The problem here is that somehow AI is exempt from these well-established copyright laws, and what they are doing with the 183,000-plus books is plagiarism,” Barnstone said.

AI is taking art by various creators, she said, and mashing it all together without attribution to create writing that is mediocre at best.

“And when the art is good or excellent, it will be because they stole not only from Grisham and [Stephen] King but from Shakespeare and Sappho and lil ol’ you and me,” Barnstone said. “It’s a violation of art not only against the individual artists but against an ecosystem of artists in which we influence each other, and human knowledge and innovation grow.”

Brad Jones, co-founder of Carefully Crafted LLC, creators of the Hey There AI platform, noted source material can be hard to track. A work of literature may be used as source material, but so might reviews, fan fiction or discussions of that work.

“Wouldn’t that be common practice, to try to mimic some of the greats – to put your own spin on it and borrow from or be inspired by other artists?” he said. “That’s how AI tools function. They come up with their own variations of those things.”

That doesn’t mean there’s not a case there, he said of the Authors Guild lawsuit and similar court cases. Even so, the work AI produces is in no way a perfect replication of the source material.

“It’s probably going to take a long time to figure things out,” he said. “If it goes one way, they may have to figure out ways for artists to pull some of their works out of the models.”

This is already happening with some visual art, he said.

But AI is getting better and better, Jones said, and its improvements are outpacing the courts.

“I think that’s happening fast,” he said. “When these things are settled, I think it will be too late in a lot of ways.”

Jones said he believes fear is what’s driving the legal action.

“For so long we thought robots would be taking our jobs on production lines,” he said. “It turns out, it’s coming after jobs we didn’t think it could touch.”

Moseley’s Discount Office Products was purchased; Side Chick opened in Branson; and the Springfield franchise store of NoBaked Cookie Dough changed ownership.